About

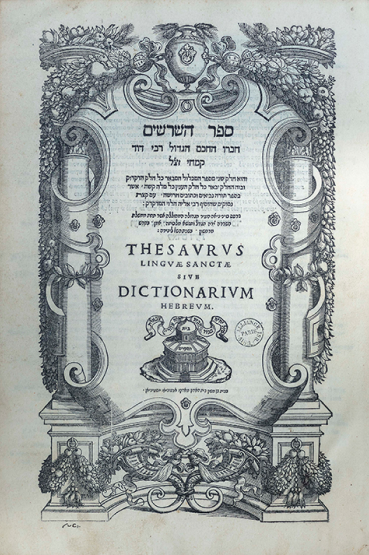

DAVID QIMḤI (Narbonne, c. 1160-1235)

A grammarian and lexicographer of Hebrew, exegete, and polemicist also known by the acronym “RaDaQ,” David Kimhi was the son of an erudite scholar named Joseph Kimhi (1105-1170) who was forced to flee Spain for Provence by Almohad persecutions. His elder brother, the grammarian Moshe Kimhi (1127-1190), was his teacher. As a teacher himself, David Kimhi offered (by his own account) Talmudic courses to young people and felt driven to write instructional manuals. During the controversy surrounding Maimonides’ book, Guide des Egarés (which some rabbis wanted to ban under pain of excommunication), David Kimhi joined Maimonides’ supporters and traveled to Spain (1232) to attempt, with little success, to recruit rabbis and scholars for the rationalist cause. In addition to grammatical and lexicographical writings, he also authored important commentaries on the Bible, including some that were openly critical of Christian interpretations.

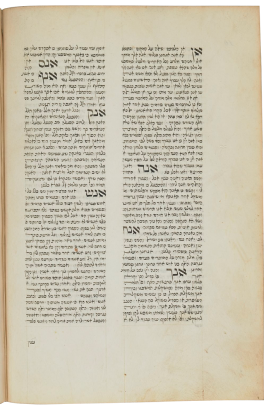

David Kimhi’s linguistic book, the Sefer mikhlol, consists of two distinct sections, a grammar (ḥeleq ha-diqduq) – commonly called Mikhlol – and a dictionary, the Sefer ha-shorashim (ḥeleq ha-ˁinyan). The author justifies the term mikhlol (which occurs in the Bible (Ezekiel) with the meaning “perfection”) as follows: “I name this book mikhlol [perfection, completeness, or sum] because I wanted likhlol [to include the entirety of] the grammar and lexicon of Hebrew in an abridged form.”

Although inspired by Kitāb al-Tanqīḥ of Jonah ibn Janaḥ (11th century), of which a Hebrew translation by Judah ibn Tibbon (1120-1190) would have been available to\ Kimhi, his objective was pedagogical. Indeed, the Kimhi Sefer ha-shorashim differed from earlier works in joining a broader movement, with a parallel in the Latin world, of linguistic books for audiences outside of a small circle of literate individuals. He described his teaching approach in his general introduction to Mikhlol, specifying that his goal was not to innovate, but to reorganize linguistic knowledge of Hebrew grammar and lexicography in order to facilitate learning. As he phrased it, his sole ambition was to be a “gleaner who followed the harvesters.” Kimhi undertook the task as a genuine lexicographer, planning every detail of the book including the future audience (talmidim, “students,” Kimhi [1842], f.1r), a taxonomy, and different clusters of information in answer to anticipated questions from reader. While the choice of lemmas was linguistically circumscribed, the internal organization of the entries was his, the order is invariable and follows the parts of speech (verbs, nouns, and particles). Kimhi decided to cover only morphological aspects of words (verbal and nominal patters, with the addition of affixes) and, unlike his father, was not concerned with theory and logical categories. The metalanguage that he used was explicit and highly condensed to make it easier to consult.

Gilles de Viterbe (Viterbe, 1465? - Rome, 1532)

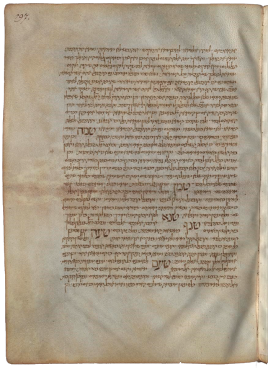

A theologian, humanist, and poet, Giles de Viterbo became the General of the Order of the Augustines in 1503 and was later named Cardinal in 1517. His great interest in the sacred language was not motivated by purely philological interest or a desire for a more effective method of Biblical exegesis, but in order to penetrate the mysteries of the Kabbala. To this end, Giles de Viterbo acquired a number of Hebrew manuscripts and surrounded himself by Jewish scholars or converts whose mission was to collect, copy, and translate them into Latin or the vernacular language. Most classical medieval Jewish mystical texts were also translated, annotated, and commented in Latin by Giles de Viterbo. At least four copies of the Latin translation of the Sefer ha-Shorashim, the Liber Radicum, and a glossary of Hebrew-Latin roots were produced within this circle, which included both Jewish and Christian scholars.

Several European libraries contain Hebrew manuscripts that belonged to Giles de Viterbo and hold brief Latin annotations in his handwriting as well as his signature. The Biblioteca Angelica in Rome and the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris possess important collections of signed manuscripts as well as translations undertaken by Giles de Viterbo.

Élie Lévita (Eliahu Bakhur, ben Asher ha-Levi Ashkenazi,

1468 or 1469 - 1549)

Born in Neustadt, Levita probably left Germany for Italy in the final decade of the fifteenth century. He quickly acquired a reputation as a grammarian in the cities in which he lived, which included Venice, Padua, Rome, and again, Venice. In 1507, he wrote a commentary on Moshe Kimhi’s descriptive grammar, the Mahalakh sheviley ha-da’at, a concise teaching manual intended to teach his students the rudiments of the language. His encounter with Giles de Viterbo (in 1515 or 1516) in Rome oriented the rest of his career and ultimately proved to be an important influence on the teaching of Hebrew linguistics to humanist scholars. Levita lived for many years in the theologian’s palace in Rome (1514-1527) and became the principal teacher of Hebrew culture to Christian notables.

In engaging Levita’s services, “a German grammarian who possesses all of the mysteries of grammar and writing,” Giles de Viterbo sought to learn not only the secrets of Hebrew literature, but he also expected Levita to compose books required to master Hebrew linguistics. Three textbooks resulted from these lessons: Sefer ha-harkavah, Sefer ha-baḥur, and Luaḥ ha-pe’alim we-ha-binyanim. The use of Sefer ha-shorashim as a teaching method left little doubt that Levita based his approach on the linguistic knowledge discussed in the book.

A man of many activities, Levita was also deeply involved in the distribution of David Kimhi’s linguistic books. Arriving in Venice in 1527 after the sacking of Rome, he earned a living as a proof-reader in the publishing house of Daniel Bomberg and helped correct and edit the Sefer ha-shorashim in the workshop of Daniel Bomberg and later that of Giustiniani. In Isny, Germany, where Levita joined the humanist Paul Fagius (c. 1539) for a while, he continued to pursue his lexicographical scholarship by publishing the Meturgeman (1541) and the Tishbi (1541). These books positioned him in line with his predecessors, David Kimhi and Nathan ben Yehiel of Rome (1035-1106), the author of the Talmudic lexicon Arukh.

First Editions

The fact that David Kimhi’s Sefer ha-shorashim was one of the first Hebrew books ever printed underlines its importance in the teaching of Biblical Hebrew and Biblical interpretation. Eight known editions were published between 1469 and 1547 that can be grouped into three categories: incunabula printed in Italy, editions produced in the Ottoman Empire, and Venetian editions. The Venetian texts illustrate the interest of Christian Hebrew scholars for the Hebrew language and the growing influence of Kimhi’s books in the transmission of Hebraic linguistic knowledge.

Three editions of Sefer ha-shorashim, one Roman and two Neapolitan, are known to have existed prior to 1500: the first incunabula was printed in Rome [Rome: Obadiah, Manasseh and Benjamin of Rome, between 1469 and 1473]; the second edition, printed in Naples by Azriel ben Joseph Ashkenazi Gunzenhauser, dates from Elul 5250, i.e., between August 18 and September 15, 1490; the second Neapolitan edition was overseen by Joshua Salomon Soncino for Isaac ben Judah ben David de Quatorze and dated 5 Adar 5251 [February 10 or 11, 1491]. Printed in two columns, it probably served as a model for subsequent editions.

The Ottoman Empire, another important center of Hebrew printing, produced two editions in the sixteenth century, one that was published by Samuel Rikomin and Astruc of Toulon (1513) in Constantinople, and the other in Salonika, probably before 1530. The latter is the work of the celebrated printer Gershom Soncino (who died in 1534), who was apparently forced to leave Italy and who continued to print, first in Salonika (1529-30) and later in Constantinople (after 1533).

The three subsequent editions were prepared with the assistance of Elia Levita, who arrived in Venice in 1527 after the sacking of Rome and helped corrections for publication of Sefer ha-shorashim, prepared by Isaiah ben Elazar Parnas on the presses of Daniel Bomberg in 1529.

The second Bomberg edition was published in February-March 1546 under the direction of Cornelius Adelkind. This edition differed only slightly from the 1529 edition.

Six months later in October 1546, the printer Marco Antonio Giustiniani republished the Hebrew text of the 1529 Bromberg edition, adding Levita’s remarks (nimmuqim).

Elie Levita’s multiple activities as grammarian, teacher, and editor-corrector are closely linked to these publications. The 1529 editions were published shortly after his arrival in Venice, and those of 1546-1547 after he returned from Isny.